1905 American Elimination Trial

First Elimination Trial to select five American cars to compete in the 1905 Vanderbilt Cup Race

Location: Nassau County, Long Island , New York

Date: September 23, 1905

According to the Vanderbilt Cup Race rules, America could enter a maximum of five automobiles in the 1905 race. On September 23, 1905, the American Elimination Trial was held to determine the five entries from 12 American candidates. A four-lap race totaling 113.2 miles was to be held over the new course.

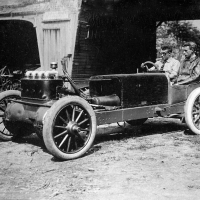

A wide variety of American cars were entered, including the 90-hp Locomobile and a 60-hp Pope-Toledo, which had both participated unsuccessfully in the 1905 Gordon Bennett Race held in Europe; a 40-hp White Steamer developed by the White Sewing Machine Company; and a unique front-wheel drive Christie. Two cars eliminated themselves before the start of the race; the Matheson did not start and the Premier was ruled overweight. The Premier was to have been driven by Indiana daredevil Carl Fisher, the future developer of Miami Beach, Montauk, and the Indianapolis Speedway.

The Start

Normally quiet and remote Mineola, the town nearest the 1905 Vanderbilt Cup Race’s start-finish line, was unusually abuzz the night before the American Elimination Trial. With log campfires blazing the Long Island Automobile Club camped out in tents. Guests had an ample supply of food and drink including a “midnight lunch” of sandwiches, cake, cheese, crackers, tomatoes and Bartlett pears, all protected in wax paper.

Breakfasts as early as 3:30 and 4 a.m. were the rule on Saturday, September 23 and shortly thereafter Jericho Turnpike filled with motorists. The mid-September weather was pleasant but most spectators were seen well wrapped for the morning chill. A good crowd was on hand but, as expected, it fell well short of what was anticipated for the upcoming Vanderbilt Cup Race. By most accounts, the grandstand was about half full, with thousands more lining the course. Men outnumbered women by a wide margin.

The scheduled time for the race was 5 a.m. but was bumped back 30 minutes during which time officials cleared the course, organized the contestants and issued instructions to all with active roles. Other than officials and contestants, photographers were allowed to remain on the course to record the start. Starter Fred Wagner shouted to Frank Nutt, who sat first in line with his Haynes racer, “Get ready, Nutt. You’ve got exactly 5 minutes.”

Wagner continued the countdown by the minute until there was 1 minute left. He counted further in 10 second intervals, down to the final 10, when he ticked them off one-by-one.

When the time came, Nutt’s departure was described as cautious, as he apparently fumbled with his clutch. The sunlight struggled to break through and illuminate the setting as dawn was still not due until shortly before 6 a.m. Nutt descended down the slight grade from the summit, where makeshift seating stands stood.

Exactly 2 minutes later, Dingley, after receiving Wagner’s signal, displayed composure and confidence, quickly throwing his Pope-Toledo into gear and scooting away. He was in his high-speed gear within 30 feet of the tape.

Italian Ralph Mongini in a red sweater looked less a chauffeur than the other drivers, who wore leather or linen “dusters” commonly associated with automobilists. Mongini’s Matheson got away quickly but appeared to falter when he shifted into high gear further down Jericho Turnpike.

Next up was the quiet-running White Steamer, vastly different than the gasoline exploding engines of the other cars. Hopes were high for the American steamer. Walter White had wrecked the car in a practice run just the previous day, slamming into a telephone pole. The team had scrambled to ready the car for the race as it required extensive repairs.

Motor World reported that one of their writers caught a glimpse of the unique car’s steam pressure gauge at the start and it indicated 1,200 pounds – judged to be extreme. The steamer shot forward but had traveled a mere 20 feet before failing.

The car coasted downhill about 100 yards further before stopping with a broken toggle joint. A crowd surrounded the stricken machine and mechanics labored 29 minutes to cannibalize a touring car for a replacement part.

In the meantime Joe Tracy sat in the big, red 90 horsepower Locomobile, its engine silent. There was some drama as his mechanician Al Poole turned the crank twice with no luck starting the machine. Designer Al Riker adjusted the spark lever and another turn of the crank produced a roaring engine at last.

The experienced Tracy engaged his clutch and was among the smoothest passing through his gears. He and Poole were distinctive with handkerchiefs pinned to their leather caps blowing back in the breeze. The handkerchiefs had a utilitarian purpose: to clean their goggles.

The strangest start came from perhaps the strangest car, the front-wheel drive Christie with driver George Robertson. A minute after Tracy’s departure, a small group of men led by J. Walter Christie, rolled the car back about 15 feet from the tape. Then they pushed it forward to attempt the start, which failed. They pushed it back again, this time to about 25 feet, and then tried another push start. The engine cylinders finally ignited, just before the tape, and only seconds before their start time.

The Royal Tourist, the eight cylinder Franklin, the Thomas and the second Pope-Toledo all got away without incident. Ten cars had been started in 2 minute intervals, the first at 5:30 a.m. and the last at 5:48.

Lap 1

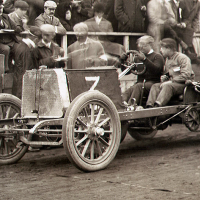

The Pope-Toledo team set the pace in the first lap by pulling off passes to run first and second by the time they passed the start-finish line again. Leader Bert Dingley not only ran the fastest lap but also passed the first racer, Frank Nutt in the Haynes. That meant Dingley not only led the lap but also was the first car to return to the start-finish line.

Dingley had cut Nutt’s 2 minute head start in half by the time they reached the first turn at Jericho. Just about 60 feet before the next turn at East Norwich Dingley edged his Pope-Toledo past Nutt’s Haynes and became the first car to reach that corner. Dingley’s first lap was the fastest of the race at 27 minutes and 58 seconds averaging 60.7 miles per hour.

The most exciting exhibition of driving skill the grandstand spectators saw all day came from Herb Lytle in the second Pope-Toledo. Instead of the traditional announcement, “Car Coming,” the megaphone-armed announcer Peter Prunty shouted “Two Cars Coming,” as Jardine in the Royal and his fast approaching pursuer Lytle in the big Pope-Toledo came into view.

Despite Lytle’s approach, Jardine remained in the center of the road, making things more difficult and dangerous than necessary. Fifty yards from the grandstand, Lytle swung his Pope-Toledo abruptly to the left and into the softer, less compact soil adjoining the road. He never slowed, and easily dispatched with the Royal to claim the center of the road in front of Jardine.

Spectators cheered and applauded the breathtaking move. No one was more anxious than William K. Vanderbilt Jr. who stood on the side of the road Lytle had decided to pass on. Understandably concerned, Vanderbilt nearly scaled the press box wall in fear for his life.

Besides the White steamer’s disastrous start, the first lap produced two additional mechanical casualties. Both the Christie and Matheson entries met with setbacks.

George Robertson in the Christie suffered tire failure and destroyed a wood-spoke wheel in the first turn at Jericho. Reports indicated that he took the turn too fast and ran into a ditch. Both tires were ripped off.

Robertson telephoned the referees for permission to change the wheel and after some deliberation he was allowed to do so. The process required an hour as he fell hopelessly behind. Reports suggested that the tire failed because it was under-inflated and the rim was destroyed when Robertson drove it 250 yards to the nearest tire station.

The Christie was the only car to experience tire failure in the race, noteworthy given the excessive number of tire punctures in the 1904 Vanderbilt Cup Race. What’s more, no car other than the Christie changed tires during the race.

The Matheson, driven by Mongini, suffered a fatal blow after traveling just 10 miles. The modified lubricating system failed to perform and the main engine bearing was destroyed. This was the same malady that hit his teammate Tom Cooper the day before in practice. Rolling to a stop just past Jericho the Matheson was out of the race.

When Montague Roberts in the Thomas completed his first lap onlookers noted fragments falling off the car. Examination determined it was pieces of the battery box.

Lap 2

On the second lap Dingley retained the lead and was still the fastest car despite stopping to adjust his induction coil. Teammate Herb Lytle did not fair nearly as well.

Lytle slowed for oil at the Pope-Toledo supply station at East Norwich. A crewman tossed a can of oil to his mechanician and Lytle immediately slammed the car into a higher gear and stripped his transmission. An inspection revealed a broken universal joint on the drive shaft, a split crankcase and a cracked gear case.

Emotions ran high as Lytle’s mechanician Jack Tattersall gave him an earful. The verbal abuse was sustained for several minutes and Lytle is reported to have ignored it.

Winchester in the Franklin got as far as Bull’s Head turn on his second lap before he fell out of the race. A bolt broke off the drive shaft universal joint and shot a hole in the gas tank. The big, air-cooled eight cylinder car was deemed too slow for competition.

The disappointing run of the White steamer, a crowd favorite, mercifully came to an end on its second tour of the course. The stricken car coasted silently to a stop just past the grandstand with a split water tank and a broken universal joint. The Friday practice wreck had weakened the car’s structural integrity.

Lap 3

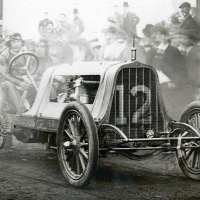

A taste of intrigue was introduced into the race in the third lap as Dingley surrendered the lead to Tracy. Dingley stopped twice for service, once for fuel and again to clean his carburetor. By picking up 3 minutes and 30 seconds on Dingley, Tracy moved the Locomobile into the lead by 4 seconds.

With Robertson’s Christie delayed again by tire failure the race was effectively down to five cars. Amazingly, Jardine in the Royal Tourist passed Montague Roberts and the Thomas despite experiencing the most hair-raising accident of the race.

Jardine’s incident happened as he headed toward Albertson just past the Guinea woods turn, the only right-hander of the course. Coming off the corner too fast he slid out to the edge of the course where piles of loose stones laid, kicked up from the tires of the other cars. The Tourist skidded sideways and turned over on its left side.

Jardine and his mechanician Tucker jumped from the car. It was good fortune that neither man was seriously injured although Tucker had a broken thumb and Jardine had gashes in his left leg. A crowd of about 100 people had gathered at the spot to watch the race and they scattered when the Royal Tourist came crashing through.

Within minutes, Jardine beseeched the crowd to right his car before all the fluids – water, fuel and battery acid – spilled out. The crowd helped him and they soon discovered that the car, while drivable, had suffered a bent steering wheel, broken seats, and the loss of its radiator cap. The men worked to straighten the steering wheel and some other levers and then stopped at a service station in Lakeville for gas and water.

Lap 4 - The Finish

Dingley pushed his 60 horsepower Pope-Toledo hard in the final lap, recording his second fastest tour of the course. He gained more than a minute on Tracy in the Locomobile who finished 59 seconds behind despite never stopping for service during the race.

Dingley no sooner crossed the finish line at 7:32:50 a.m. than timers and spectators began their calculations to determine how much time Joe Tracy could afford to take to complete the fourth and final lap and still win the race.

Through the telephone network Tracy was reported at New Hyde Park and it became apparent he could not win as he had 3 miles to cover, and only 2 minutes to do it – impossible at the speed he was averaging. Factoring in Dingley’s 6 minute head start, Tracy’s finish at 7:39:49 a.m. left him 59 seconds short of the Pope-Toledo driver.

With the winner apparent the crowd became more difficult to control. The next finisher was Frank Nutt in the Haynes who actually ended up in fourth place despite being the third car across the finish line. Jardine’s Royal Tourist took third place honors as he made up more than 2 minutes of Nutt’s 12 minute head start.

The only other car to finish was Roberts in the Thomas who limped across the line at 8:13:40 a.m. with only two cylinders working. Thomas mechanician Frederick Grant spent most of the race holding the car’s batteries after the battery box fractured on the first lap.

The only other car on the track was the struggling Christie and a phone call to the station at Jericho brought out a flag to end driver Robertson’s day. The top five finishers were ordered to the scales at Albertson for a post-race weigh-out.

While waiting for the Pope-Toledo to be weighed the victorious Bert Dingley said, “I drove the Pope-Toledo as well as I knew how and as it is a stanch car and a true one it stood by me. I knew all the time it had the speed but feared trouble with my oiling, as was the case abroad (the July Bennett Cup Race). I did not know I had won until I had been off the course for some time. I was too early a starter to take any chances of getting behind.”

Locomobile driver Joe Tracy added, “The course was in good shape in the main but there seemed to be a lack of bottom to the roadbed. The other problem was on Jericho Turnpike and was due chiefly to rough stone. At these points I had to slow down to about 40 miles per hour. I did not get all the speed out of the Locomobile that it was capable of. I did not try to do so. What I wanted to do was to qualify and I did not particularly care whether I won this race or not. The coming struggle is the one I am after.”

American Team Selection Controversy

Weeks in advance of the American Elimination Trial the race commission released a statement with respect to the selection of the American team for the Vanderbilt Cup Race saying, “The commission reserves the right to select the five cars which, in their opinion, make the best showing in the trial.”

An unidentified commission member elaborated, “…we put forth this reservation to enable us to use our discretion should an extreme case arise…such a case, however, is not likely to occur and the order of finish, except some such an extreme instance, will undoubtedly determine the selection of the team.”

Unlikely or not the race commission did use their discretion in a highly controversial decision at the AAA New York offices Monday evening, September 25, 1905. They released word that the Royal, Haynes and Thomas teams would be denied the honors they thought they had earned with their on-track performance by finishing in the top five places. Instead, three poorer performing cars took their place on the American team.

The Pope-Toledo of Herb Lytle, the White steamer and the Christie were selected to join Dingley and Tracy on the American team for the Second International Race for the William K. Vanderbilt Jr. Cup. Due to a belief that driver George Robertson was too inexperienced a stipulation was also placed on the Christie team that designer Walter Christie must drive the car. Family pressure had persuaded Christie not to drive the car in the American Elimination Trial.

Ostensibly, the decision was made on the grounds that the Pope-Toledo, White and Christie cars had encountered chance misfortune and were truly the best of the field. Commission Chairman Morrell released this statement: “It’s no snap judgment. Before the matter was discussed or voted upon, at my request Mr. Breese and Mr. Riker left the room…remember, we considered that we represented the American public. We felt it our duty to select the five cars which, in our opinion, were most likely to keep the Vanderbilt Cup in this country.”

The reference to Race Commissioners (capitalized as a personal title preceding the name) James Breese and A.L. Riker was because of their association with two of the teams and a conflict of interest. Breese entered the Christie car and Riker designed the Locomobile. If Breese’s attitude is reflected in one of his newspaper quotes one can assume he only exacerbated the situation with his answer to a question asking the reason for the decision. He was quoted to say, “Reason? We give no reason; we just did it.”

Criticism flowed freely from the media, and the discarded entrants. In an editorial, The Motor Way printed, “…the American Automobile Association – reserves the right to do as it damn pleases regardless of the outcome of tests, what on earth is the use of tests? What is the use of the Vanderbilt Cup Race?”

Harry Houpt, who entered the Thomas, complained, “They have no right to take my $500 and make me spend $1,200 and then throw me out without a hearing.” The Thomas Company reinforced their displeasure with the decision by placing an ad in the official program for the 1905 Vanderbilt Cup Race. The ad read: “Qualified but eliminated from the final by edict of the AAA Racing Board… In the face of a shattered battery box finishing first lap in 30:51, the Thomas ran for three more laps and fairly won fifth place.”

Houpt’s reference to the lack of a hearing was that the owners of the disqualified entries had no chance to discuss the matter with the race commission before the latter took action. Rumors of the race commission’s plans to render the decision persisted throughout the day Monday. Afterward, Commission Secretary (capitalized as a personal title preceding a person’s name) Batchelder told The Motor World that the reason there was no hearing with the disqualified entrants was because they did not ask for one before the decision was made.

The newspapers played up the controversy and some were critical of the decision. Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal called the decision, “arbitrary.” Automobile Topics was more supportive of the race commission’s decision, pointing out that all entrants were aware going in that the commission could invoke discretion. Also, they insisted that the trial was necessary to collect the data required to make a judgment. The Motor World took a different stance, allowing for the race commission’s right to discretion, but taking them to task for choosing the Christie over the Thomas.

Another twist in the controversy was an advertisement ran by the Premier Motor Manufacturing Company. The Premier team, denied entry in the trials for exceeding the weight limit, saw an opening for consideration if the race commission was to employ “discretion.” Their ad criticized the race commission for denying the three entries that earned a place on the team, but also for refusing to even consider the Premier as an alternative entry – which they said had undergone 500 miles of testing.

The final paragraph of the ad read, “On Monday following the elimination trials, we wired the committee that our car could weigh-in, and offered it subject to any tests they might designate. We were advised by the chairman that ‘We were compelled to select the team without reference to your car.’ Is this American sportsmanship?”

Regardless, the race commission members were well beyond changing their minds. The American team for the Second International Race for the William K. Vanderbilt Jr. Cup was set for October 14, 1905, albeit in the backdrop of controversy.

The partially completed train crossing is obviously Mineola or Albertson. Staring at the picture it could easily be…