Race Profile: 1936 Vanderbilt Cup Race

A summary of the 1936 Vanderbilt Cup Race- an attempt to revive racing on Long Island.

Enjoy Super Sunday,

Howard Kroplick

1936 Vanderbilt Cup

As American economic conditions improved, Willie K’s nephew, George Washington Vanderbilt III, Boston Redskins owner George Preston Marshall, and Eddie Rickenbacker raised money to return international racing to Long Island. 1908 Vanderbilt Cup winner George Robertson was vice president and general manager, overseeing construction of the four-mile Roosevelt Raceway in Westbury. It was adjacent to Roosevelt Flying Field, where Lucky Lindy departed for a trip to Paris in 1927.

Mark Linenthal, an architect and friend of Marshall, was hired to design the course, and famous board track huckster and compulsive gambler, Art Pillsbury, was retained as consultant. Considering the results, and the fact Pillsbury lived in L.A, while Linenthal resided in New York, possibly, the two never communicated. The Vanderbilt track was a four-mile course with a single 3775-foot straightaway and sixteen completely unbanked corners, ten of which are best described as “hairpin.”

Founders envisioned a world-class facility, with wide turns, well equipped garages, massive double-decked grandstands, a posh clubhouse, generous parking and thoroughfares to deal with anticipated traffic. Like Willie K, the Roosevelt bigwigs wished to attract the east coast social set, not the dirt track fans that supported racing through the Depression.

Never sure whether they wished to revive the Vanderbilt Cup or the Grand Prize, organizers first announced a 400-mile race, then, revised it to 300, set for Columbus Day, 1936. A massive purse and personal clout attracted Europe’s top teams and America’s dirt and championship drivers answered the call.

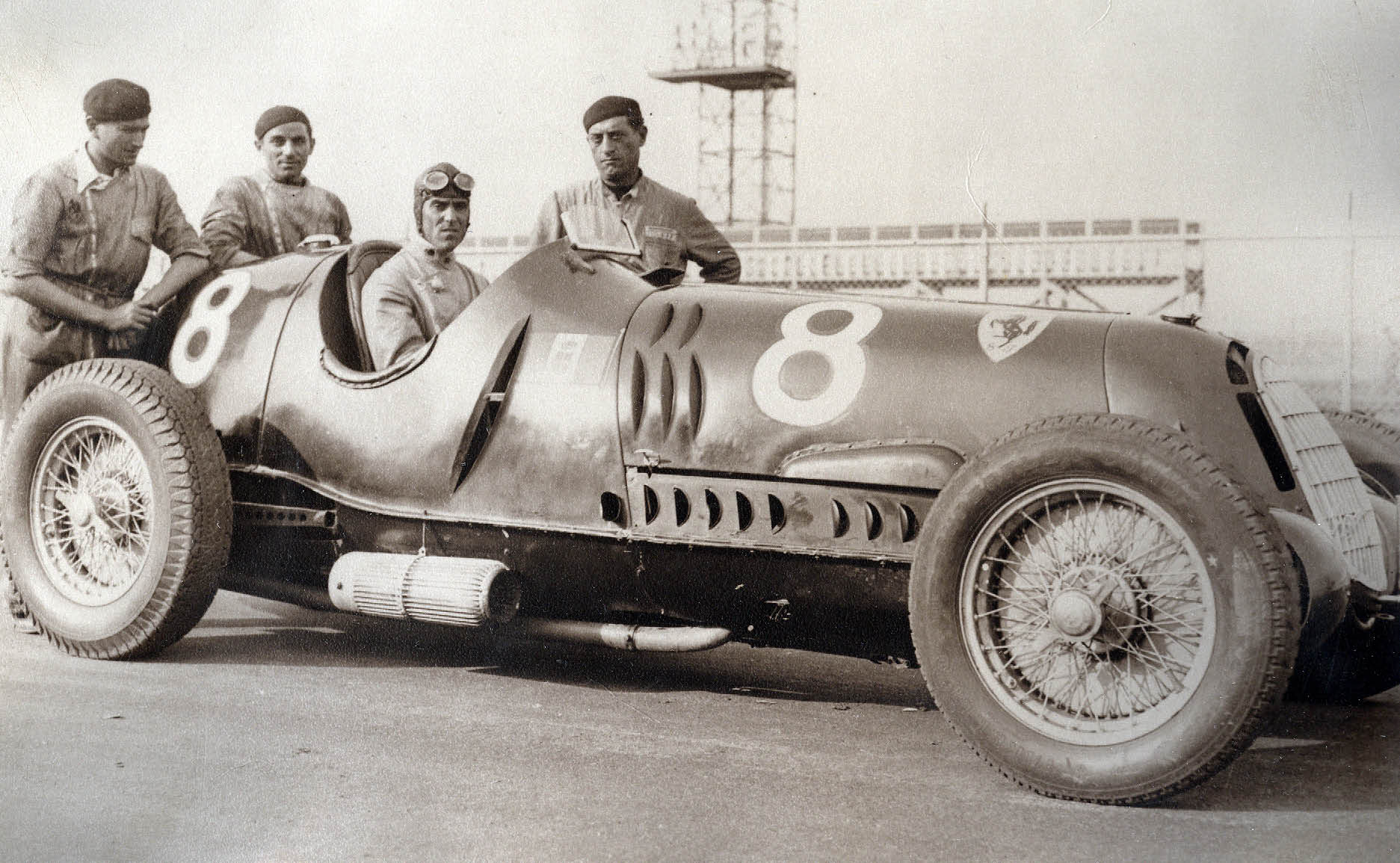

Like many manufacturers, Alfa Romeo stopped fielding a factory team in 1932. Instead, Scuderia (“stable”) Ferrari was Italy’s national team, featuring legendary racers Tazio Nuvolari, Antonio Brivio, and Nino Farino, campaigning Alfa 12-cylinder, 36-valve, 4.1 liter engines, 4-wheel independent suspensions, and 5-speed gearboxes.

Pat Fairfield, Earl Howe, and Brian Lewis started in supercharged 1.5-liter ERAs (English Racing Automobiles). Lewis had been slated to pilot his Bugatti Type 59, but Louis Meyer, bumming a ride, wrecked it in practice. Lewis took Major S.S. Cotton’s ride. Essentially on holiday, these Brits were all rich kids, and amateurs, ready to take on America’s dirt track pros, often, with twice the engine displacement.

At the time, the only way for European teams to come to America was to ride the boat across the big pond, and they did. Three more Bugattis and four Maseratis started. The Germans played possum at the time, and the French were curiously missing.

The Americans weren’t. Wilbur Shaw’s “money car” qualified for the front row. American dirt cars did well in qualifying. Ted Horn ran his Stevens-Miller, as did Jimmy Snyder and Tony Gulotta. Floyd Davis, George Shafer, Bruce Carew, and Russ Snowberger brought Rigling chassis, derived from the Studebaker Indy cars. Frank Brisko piloted the Four-Wheel Miller that he spent three years of his life fixing. The Chicago contingent, Henry Banks and Emil Andres, campaigned Emil Diedt’s designs. Four Duesenbergs qualified. Wild Bill Cummings, Shorty Cantlon, Joel Thorne, Babe Stapp, and Billy Winn all showed up to represent their country.

Armed with toenail clippers, the Americans marched into the gunfight at the OK Corral. Ignoring the fact that AAA cars used one or two gears, and crude, stiff suspensions, the speedway racers were still two-man cars, often, twice the size of the European entries. The dirt cars weren’t supercharged, and ran at a disadvantage of 200 hp down the one long straight, where a faster car could gain an advantage.

In practice, no one could turn a lap above Nuvolari’s 69.9 mph. The local press mused that motorists traveled faster on the Long Island Motor Parkway than the pros could muster on the brand new Roosevelt Speedway.

Although Americans sat in the front rows for the 1936 Vanderbilt Cup, the sporty European cars quickly came up to speed. Count Antonio Brivio set the target for the twenty-mile qualifying run, with an average speed of 67 mph in one of the Alfa Romeo supercharged 4.1 liter Grand Prix cars. Dirt tracker Billy Winn showed the visitors how to slide through the turns to take 2nd spot. Wilbur Shaw’s catfish-faced “money car” could only turn left, but lined up 3rd. Americans George Connor, Deacon Litz, Al Putnam, and Phil Shafer took the next four spots, all with big two-man Indianapolis cars. The slowest of the forty-five qualifiers was Lewis Balus’ Duesenberg, at 56 mph.

The Italians caught up the next day. Tazio Nuvolari completed his run in 17:09.62, just a tick under 70 mph in another Alfa. On pole day, Nuvolari’s transmission had failed. His teammate and protégé, Nino Farina, was fifteen seconds behind. The Bugattis, Maseratis, and the Brittish ERAs continued to struggle.

Nuvolari’s fame was unmatched in Italy, where they loved fast cars as much as Americans loved baseball. The Flying Mantuan captured the 1932 European driving title for Alfa Corse. When Alfa decided they had nothing left to prove, and stopped sponsoring the factory team, Nuvolari piloted Maseratis. For the 1935 season, he returned to team Ferrari. There were rumors that Enzo Ferrari didn’t want the high profile driver, but Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini persuaded him.

The 12-cylinder Alfa was an old design and the new German cars were faster. Developing 370 hp at 5800 rpm, they weren’t as powerful as the Miller engines in the Indy cars, but were more than six hundred pounds lighter, and more aerodynamic, due to the small outline. The four-speed gearbox, independent suspension, and oversize brakes were a huge advantage on the Roosevelt Raceway hairpin curves.

Nuvolari was described as determined, iron-willed, and incredibly athletic. On May 8, practicing for the Tripoli race, he cracked two vertebrae in a practice wreck. He raced the next day in a body cast. Also seldom mentioned is that Nuvolari dropped a cylinder a few laps into the Vanderbilt Cup race.

The “Madman from Modena” was an Italian hero because he ignored adversity, and stepped up to each challenge, even to the impossible. He was coming off a season of wins at Nurburgring, Barcelona, Budapest and Milan against the mighty German Mercedes and Auto Union teams. After a newspaper erroneously reported his death, Nuvolari quipped, "When someone announces my death, you have to wait three days before crying. Everything is possible!" The Vanderbilt Cup was over when Nuvolari stepped off the boat.

Billy Winn gave the American fans someone to cheer. With a single gear and no brakes to speak of, Winn didn’t bother to slow for the curves, and loved to hound the Italians, who quickly pronounced him “crazy.” For the first 17 laps, Winn and Farina staged a spirited game of “chicken” for 3rd, until Mr Wall grabbed the Italian on the west curlicue. With no chance of catching Nuvolari, or Jean-Pierre Wimille’s suddenly potent Bugatti, Winn held stride until lap 64 of 75, when a blowout doomed him to 28th. One of only two Frenchmen to enter, Wimille sported a Roots-supercharged 4.7 liter engine capable of 400 hp, but old leaf-spring suspension. The same car, allegedly, won Paris’ Coupe des Prisonniers, the first European race after WW2, in September of 1945. Wimille died racing in Argentina, three years later.

Shaw was first out, crashing on the second lap. Nuvolari led all 75 laps, the fastest above 70 mph. For four and a half hours, he never missed a shift, averaging an incredible 66 mph. Wimille trailed by more than eight minutes and two laps, with Brivio another lap down.

Wild Bill Cummings was the first American to cross the line, twenty-five minutes behind. Attendance was estimated at 50,000. New York millionaires were tough to find in 1936. Clearly, changes were necessary for the Vanderbilt Cup to survive on Long Island.

This view of Roosevelt Raceway looking east was photographed during the running of 1936 Vanderbilt Cup Race.

The course was four miles long with 16 turns.

Tazio Nuvolari and his Alfa Romeo racing team.

At the start of the race.

A view of the grandstands at the first turn.

Tazio Nuvolari at speed.

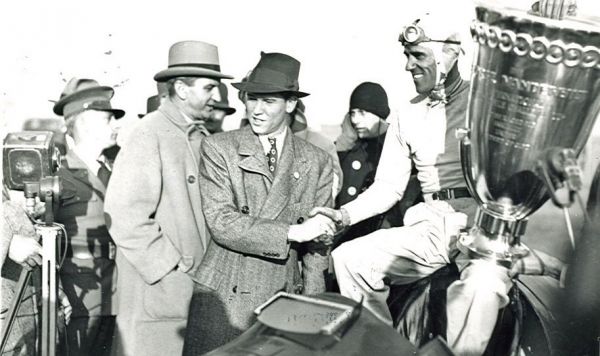

The winner Tazio Nuvolari receiving his Vanderbilt Cup replica from George Vanderbilt III.

Comments