Ford.com: Falcon vs Ferrari? Yes!- The Holman-Moody Challenger III

Ford Motor Company has posted this comprehensive article on the Challenger III on their Ford Performance website.

John Katz' article provides the most comprehensive information ever assembled on the Challenger III.

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

____________________________________________________________________________________

FALCON VS FERRARI? YES! – THE HOLMAN-MOODY CHALLENGER III

APR 27, 2023 | BY JOHN F. KATZ

UPDATE; 5/17/23 New photos added from article

After The Big 3 had agreed to an Automotive Manufacturers Association (AMA) resolution to officially de-emphasize corporate participation in motorsports in 1957, Henry Ford II decided to return to racing in 1962.

The AMA ban on factory-sponsored competition had proven ineffective, and in June of '62 Ford was first to officially renounce it. Already Ford engines powered the Cobra; by year's end Dearborn had revealed ambitious plans for Indianapolis and Monte Carlo, a renewed commitment to NASCAR, and, with the V4-powered “Mustang I” prototype, the soon-to-be-famous name was the company's earliest experiment with a mid-engine road-race chassis.

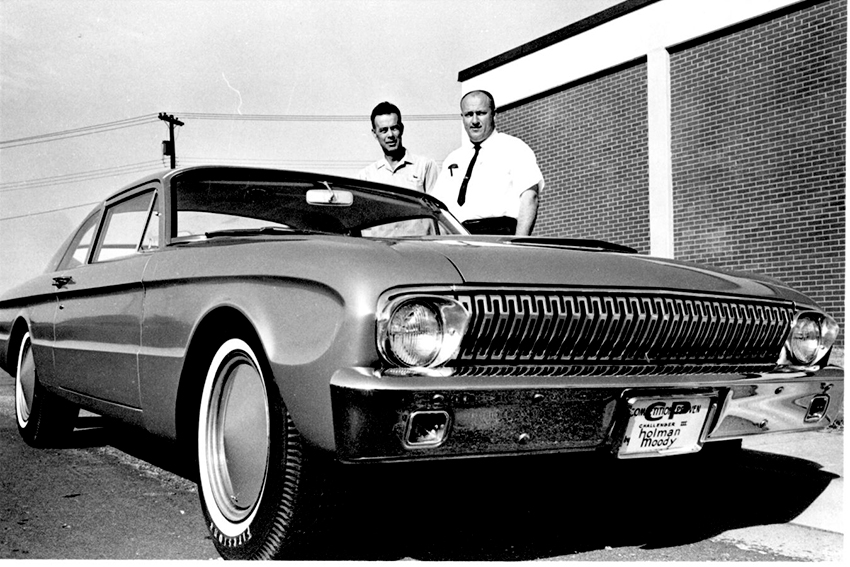

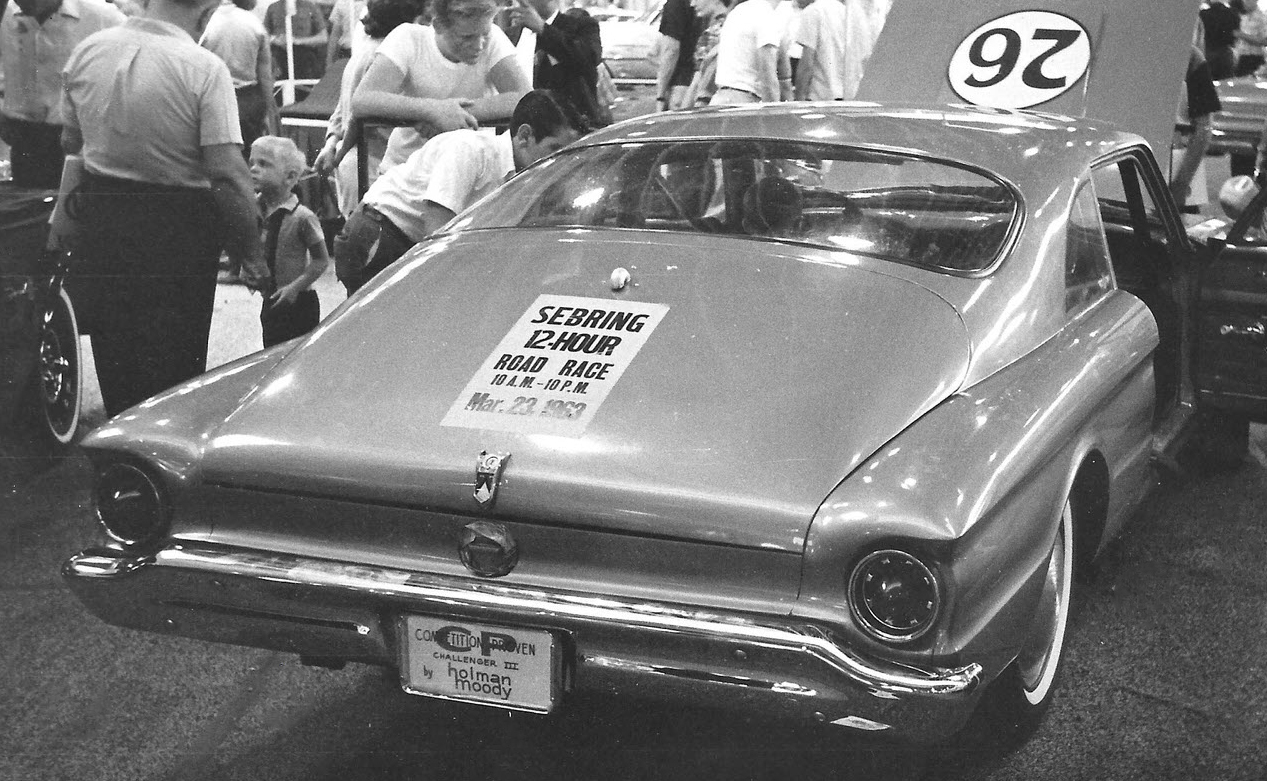

Amid all this activity – and very much a part of it – stock-car specialists Holman & Moody* cut up a Ford Falcon and reassembled it as “Challenger III:” a meticulously crafted competition GT that kept pace, however briefly, with the world's fastest sports racing cars.

In fact, Holman-Moody* built three high-performance Falcons named Challenger, almost certainly for the engine that powered them. Leveraging the latest advances in metallurgy, Ford's new “Challenger” V8 pushed down the lower limits of weight and size for a cast-iron small block. Initially a Fairlane exclusive, in 221 and 260 cubic-inch displacements, the little V8 would have been a novelty in a Falcon, where it would not become a factory option until January 1963.

For the first of the series Holman-Moody over-bored a 221 to 244 cid, just under the 4.0-liter limit for Grand Touring Prototypes, and fitted it with high-compression heads featuring oversized valves, dual valve springs and shaft-mounted rocker arms. A near-NASCAR-spec camshaft required solid lifters; and with enlarged ports topped by a four-barrel carb from a big-block 406, horsepower ballooned from the stock 145 to a race-ready 230.

A Borg Warner four-speed transmission, also 406-grade, was coupled to Ford's ubiquitous 9-inch rear axle. Stiffer springs, also lifted from a bigger Ford (sources disagree about which bigger Ford), were supplemented by racing shock absorbers and a custom rear sway bar. Brakes were finned aluminum drums from a Continental convertible, front spindles were from a '57 Lincoln, all riding on 6.70 in. x 15 in. tires. Twin 18-gallon fuel tanks, fed by a common filler, neatly replaced the back seat.

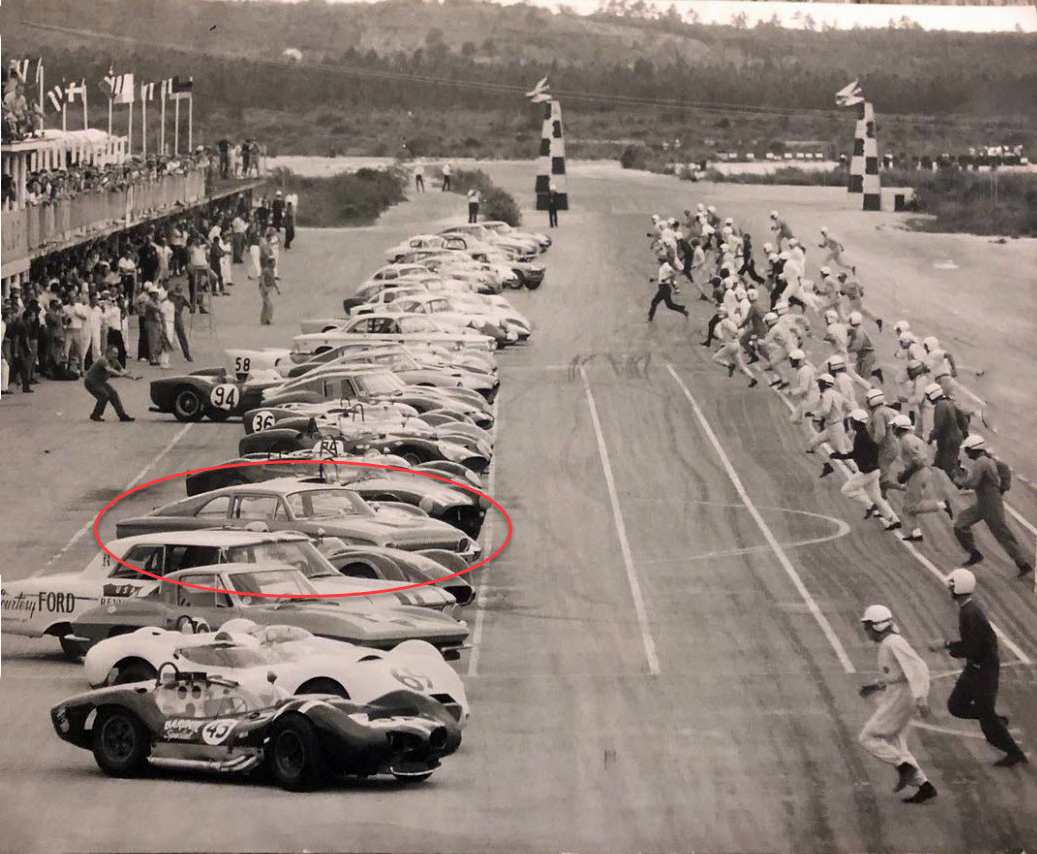

This first Holman-Moody Falcon Challenger debuted at the 12 Hours of Sebring, March 23-24, 1962, having been built from a stock Falcon in just 10 days. With limited time for testing, however, problems arose during the race. Inadequate oiling of the rocker shafts forced a mid-race re-fit of stock-style stud-rocker heads. The time lost limited drivers Marvin Panch and Jocko Maggiacomo to 36th overall – and a distant second in the Prototype class, 82 laps behind Jim Hall's Chaparral. Still, John Holman told Motor Trend that he “felt pretty good about finishing the race as we did.” And years later, Panch asked his Facebook followers if “In your wildest dreams, could you even imagine a Falcon leading a Ferrari GTO at Sebring?”

“Top speed at Sebring appeared to be about 135 mph,” added Motor Trend in July of 1962; but Holman-Moody believed a lower profile would improve both speed and handling. So they sawed a Falcon body in half horizontally, removed three inches, and put it back together as Challenger II.

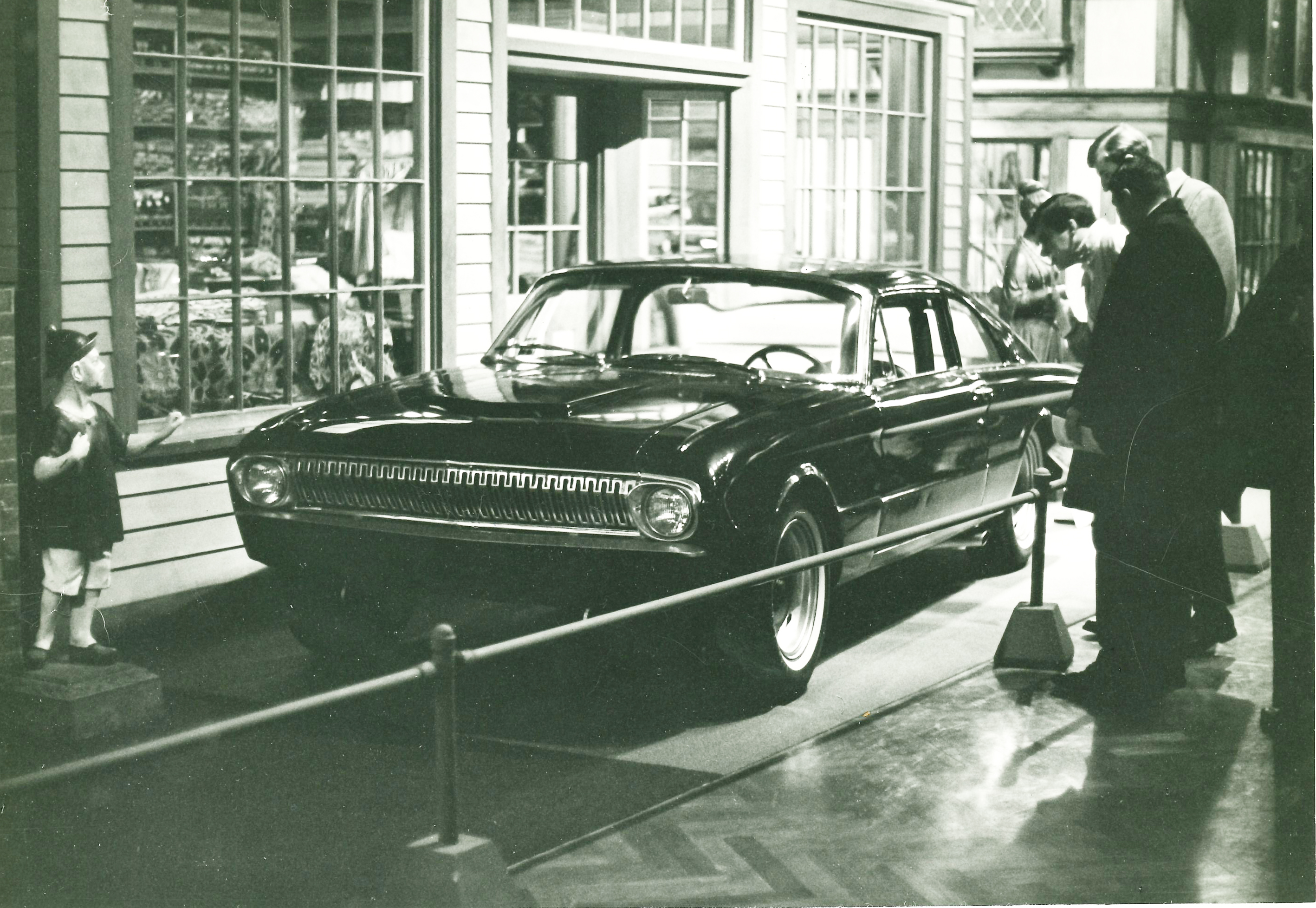

This second-phase Challenger was no race car, however. As John Holman's son, Lee, later told blogger Michael Lempert, Challenger II's mission was to probe the Falcon's potential as a high-performance road car. (After a month of road testing by Lee himself, it was delivered to the Dearborn engineering team that was developing the Mustang.) Motor Trend initially reported that Challenger II packed “the same special goodies under the hood” as the racer now called Challenger I, but in fact Challenger II was powered by a stock 260 V8, and was fully trimmed like a production car, complete with wheel covers, chromed window moldings and a mostly stock Falcon Futura interior. The chassis was considerably stiffened and featured advanced Airheart disc brakes all around. In March '63 MT recorded a 16.9-second quarter-mile at 82 mph, and repeated 60-0 panic stops in just 133 feet.

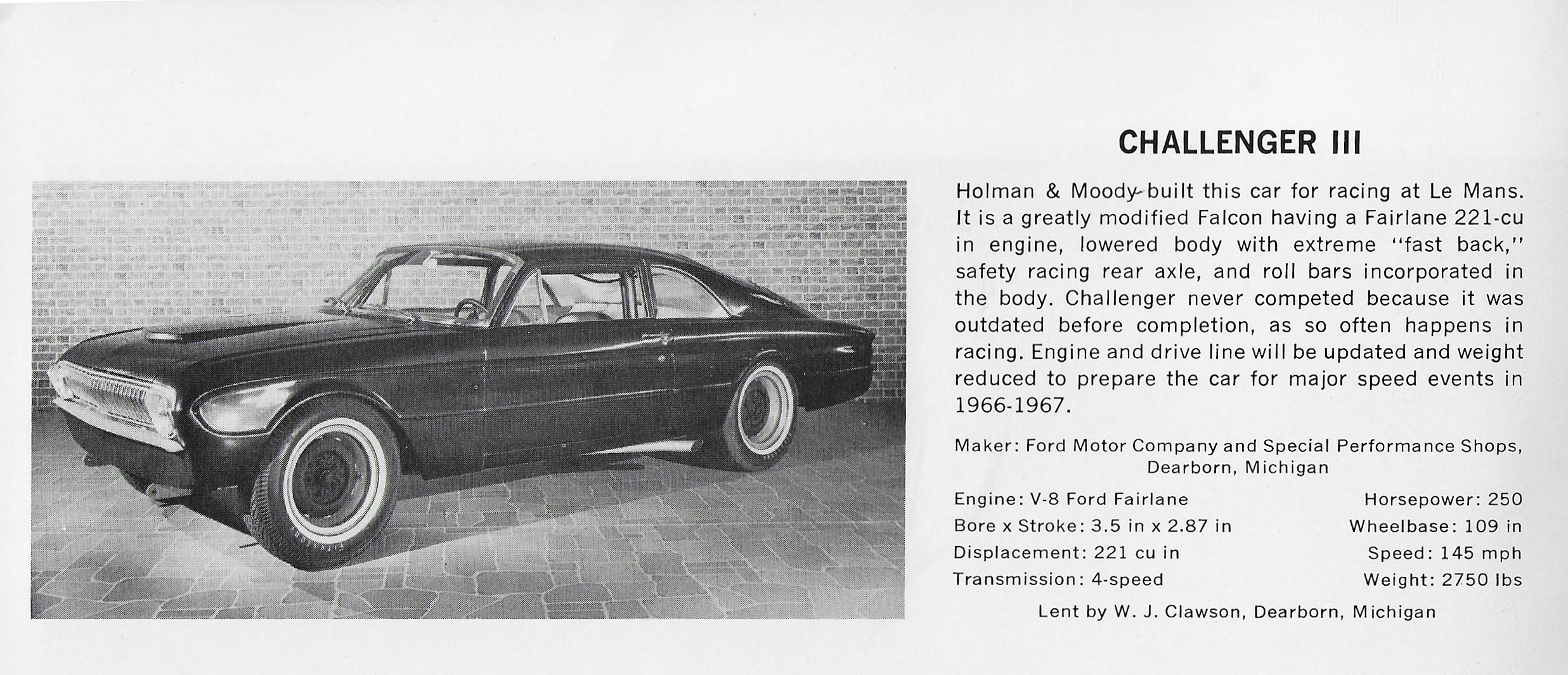

Appropriately, then, the third and final Challenger combined race-car performance with the comfort and finish of an exotic GT. Again, three inches were sectioned from the lower body, plus another three from the greenhouse, slimming Challenger III down to about the same height as a contemporary Porsche 356 or Ferrari 250 GT. A fastback roofline, custom-fabricated from sheet aluminum, tapered all the way to the rear edge of the trunk. Mechanical specs were initially the same as on Challenger I, but Holman-Moody quickly traded up to Ford's newest, 289-cid version of the Challenger V8. With the bigger engine suitably modified for racing, the ultra-low fastback reportedly topped 145 mph.

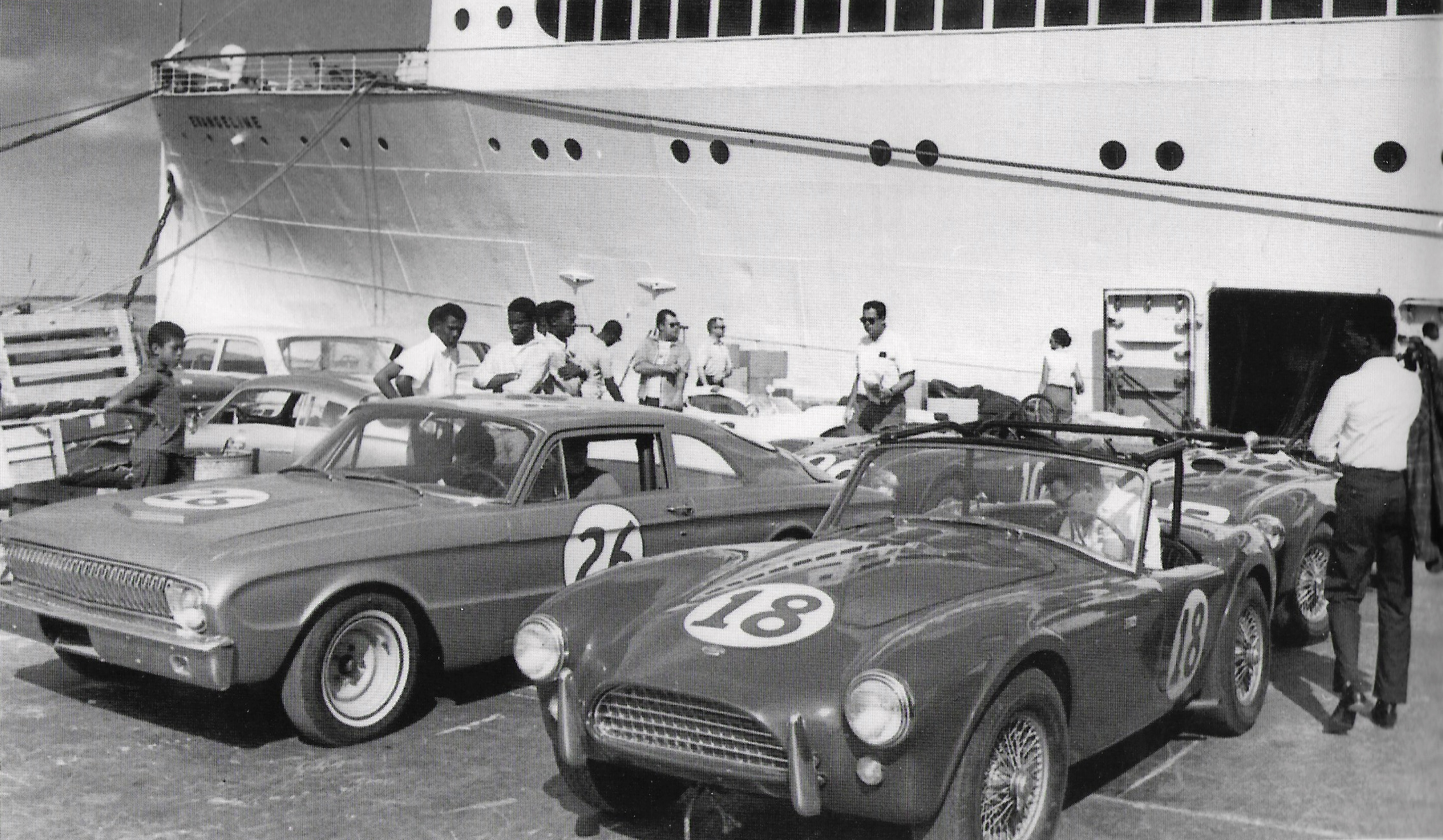

The engine swap was completed in time for the International Bahamas Speed Weeks, held December 2-10, 1962. Panch placed first-in-class and fifth overall (behind four Ferraris) in the Preliminary Nassau Tourist Trophy, and third-in-class (behind two Cobras) in the Preliminary Governor's Trophy. Results in the remaining preliminaries were disappointing, however, and Challenger III failed to finish the featured 252-mile Nassau Trophy Race. Already overheating at mile 76, it was dealt the coup de gras by a broken fan belt.

According to Motor Trend, Holman-Moody had considered a limited production run of 100 cars, which would have homologated Challenger III for GT-class racing under FIA rules. The magazine speculated that copies of Challenger I & II might also be produced for sale. But in February 1963 Ford pulled the plug on the program. All three Challengers were sold to Ford engineer and amateur racer W. J. “Bill” Clawson, for the grand total of one dollar.

Although the sales agreement mentions no such obligation, Clawson clearly lent Challenger III back to Ford for promotional purposes. Photos show the car on display at the 1963 Sebring race, its NASCAR-spec steel wheels now covered by custom Moon discs. Stripped of its racing numbers, painted a darker color – and usually without the wheel covers – it toured with the Ford Custom Car Caravan through 1965, alongside the short-wheelbase “Mustang III” (see FordPerformance.com, October 25, 2018). It also appeared in “Sports Cars in Review” at the Henry Ford Museum in 1966. The exhibit catalog specified a 221cid V8 rated 250 hp, surely an error at that point.

For several years after the Henry Ford exhibit, Clawson and his son, W. Scott Clawson, campaigned Challenger III in amateur road racing events. And according to racer and collector Ted Thomas, who later owned Challenger III for over 30 years, the Clawsons also road raced, and drag raced, Challenger I, eventually salvaging its unique Holman-Moody running gear and scrapping the worn-out body shell. Lacking garage space, they also stripped Challenger II of its mechanical parts and put the body in storage. “And when they went back to get it,” said Thomas, “everything was locked up and the tub was gone.

Only Challenger III has survived intact. In 1984, the Clawsons sold it to construction contractor Bob Bragg, who drove it on the street for a few years before selling it to Thomas – who subsequently bought the remains of Challengers I and II as well.

Howard Kroplick – whose eclectic auto collection includes the short-wheelbase Mustang III, the 1909 ALCO Black Beast, Walter Chrysler’s 1937 Chrysler Imperial C-15 Town Car, and Tucker # 1044 – was assisting Lempert with his research in December of 2020 when he learned through Lee Holman that Ted Thomas was offering Challenger III for sale. Agreeing on a price was a challenge, Kroplick told us, “because there was nothing comparable to it.” But he believes his stated desire to maintain Challenger III as show car appealed to Thomas, who “was quite concerned that if he sold it to a vintage racer, the car would not survive more than a year.”

The sale was finalized in May of 2021, and that June Howard shipped Challenger III to Ida Automotive in Morganville, New Jersey, for restoration. The grandson of a Tucker dealer, Rob Ida specializes in vintage race cars and hot rods as well as Tuckers, and had previously restored Tucker #1044 for Kroplick.

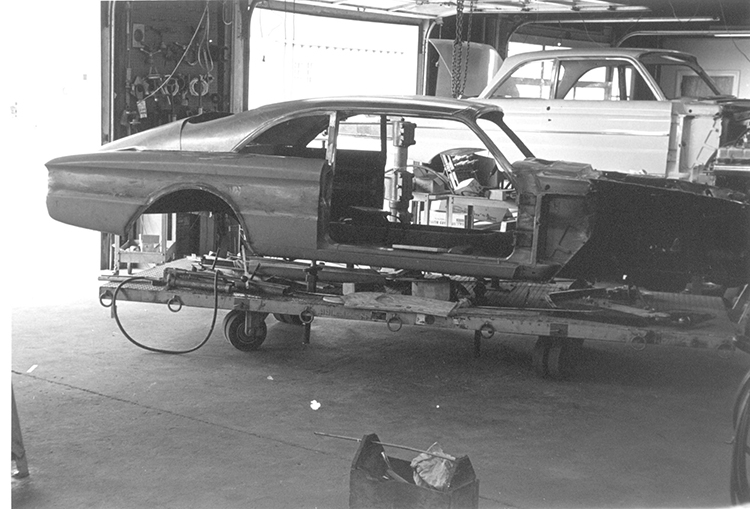

Thomas had already partially dismantled Challenger III for restoration. The body shell rolled on its wheels into Ida's shop, but much of the rest arrived in boxes –including the original Moon disc wheel covers. (Strictly for show, they lack holes for the button-head screws that would have secured them for road use.)

The restoration revealed much about how Challenger III was made. Ida marveled at the clever engineering and skilled craftsmanship. “I am a metal shaper as well,” he said, “so I really appreciated the workmanship that went into sectioning the car – because that's a lot more difficult than most people realize. When you cut a car down the center, it's difficult to get all the contours to make sense.”

“It doesn't end up being the same shape,” added Thomas, who characterized the workmanship as “phenomenal . . . Where the car was sectioned you'd have a tough time seeing where it was welded back together.

The outstanding metal fabrication that characterizes Challenger III is consistently credited to Ludwig “Lujie” Lesovsky, whom “many regard as the greatest race car craftsman ever,” according to MotorTrend.com. Born “about 1914,” per Ancestry.com., and often misidentified as “Luigi,” Lesovsky is also widely acclaimed as an innovative race car designer. A May 26, 1990, feature in The Indianapolis Star credits the “Los Angeles area native,” with the Indy-winning cars of Floyd Roberts (1938), Lee Wallard (1951), A. J. Foyt (1967), and Mark Donohue (1972). Roger Huntington, in Design & Development of the Indy Car, adds Johnny Thompson's 1959 pole-sitting roadster; and MotorTrend.com places Lesovsky at Kar Kraft during development of the GT-40.

Thomas and Ida agree that Challenger III's body was likely cut with a pneumatic “whiz wheel”-style circular saw and gas-welded back together. That much would have been standard practice; it's the planning and execution that are exceptional. “It doesn't look like they added any material,” said Ida, “which is very impressive. If they had had to patch a lot of mis-matched sections, that would tell me that they cut it first and figured it out later. But instead you can see that they made a plan, because of how well all the parts fit before any welding was done.” Ida did not find any lead in the body either, although he did find some plastic filler, notably where the aluminum roof meets the steel lower body.

Among the most challenging panels to section would have been in the inner front fenders, which on the Falcon carried the upper front suspension mounts. These had to be sectioned three inches as well, while maintaining the stock height of the shock tower relative to the lower suspension mounts, and without the shock tower poking up through the engine hood. The door boxes also had to be sectioned three inches, and new aluminum skins hand-made to pass for stock Falcon panels.

The hand-formed aluminum fastback incorporates an opening trunk lid with the factory emblem and key-operated latch – “a nice finishing touch,” Ida commented, “and when you open it up and look inside you see what looks like a factory-stamped reinforcement, like you would see in any new car, except it's all custom made.” Because aluminum won't weld to steel, the roof was attached with copper rivets. Ida was surprised that what appeared to be the original plastic filler remained intact after 60 years. “So we didn't disturb it, and that was kind of cool, because plastic filler was a very new technology at that time.”

Even the radiator grille is cut and welded back together so that the individual teeth overlap by three inches. “That had to be very tedious,” said Ida, “very time consuming. And I can see that somebody very talented executed that process. The grille and the headlight rings are polished aluminum, so you wouldn't have the benefit of using body filler to hide the welding. The welding had to be almost invisible.” The clever substitution of five-inch low beams for the Falcon's stock seven-inch lamps kept the lights in scale with the abbreviated grille. Around back, taillights from a '61 Oldsmobile look plausibly like scaled-down Falcon units, but at least six separate cuts to the surrounding sheet metal were needed to complete the illusion of stock Falcon contours.

The custom-shaped backlite is Plexiglas, as are all the side windows, although the door windows retract on the stock winders. Ida saved the badly scratched originals by hand-sanding and polishing them to restore clarity. The glass windshield did have to be replaced. which meant heating and trimming an NOS Falcon unit.

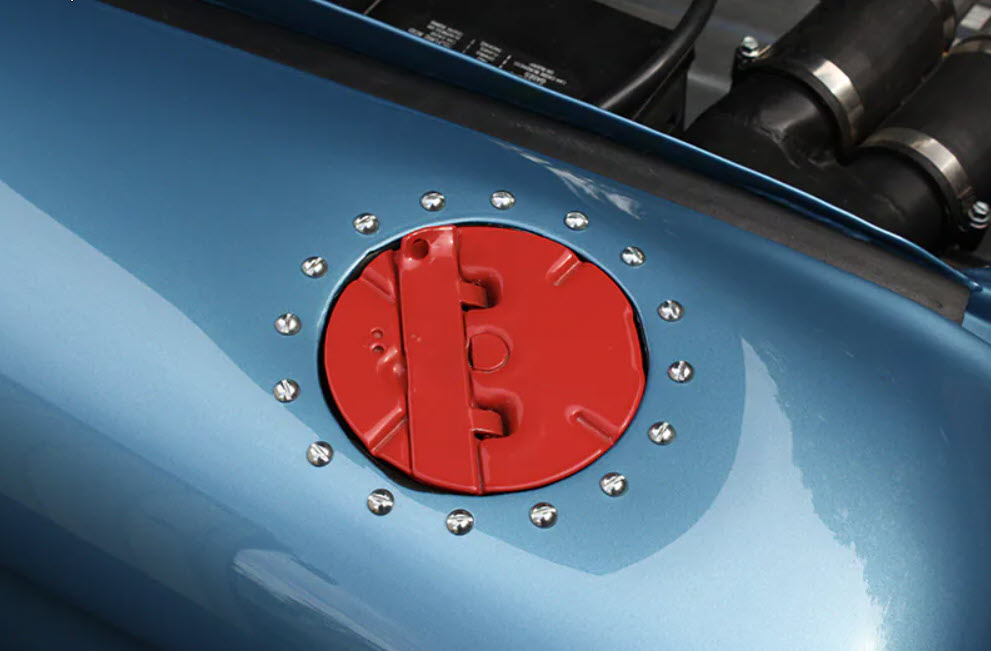

Holman-Moody's location near the Charlotte airport facilitated access to salvaged aircraft parts – such as the fuel filler caps, fuel selector valves and fuel filters on Challenger I and Challenger III. But wherever possible, Holman-Moody used off-the-shelf auto parts, modified as necessary. Challenger III's front suspension arms, for example, are made from stock Falcon pieces. “They moved pivot points and pickup points to make the car perform,” noted Ida. “They knew the magic was in the geometry.”

And where exigent, Holman-Moody used GM parts. Unique among the three Challengers is Challenger III's aluminum transmission case. Ford didn't make one, so Holman-Moody adapted one from a Corvette; they didn't even grind the Bowtie off of the casting. The aluminum cross-flow radiator is from a Corvette as well. And the seats are from a Porsche Speedster.

According to Thomas, much of the running gear under Challenger III is marked “Challenger I,” leading at least one source to conclude that the parts were transplanted from one car to the other. Thomas thinks it more likely that spares made for Challenger 1's Sebring effort were later installed under Challenger III. He owns two sets of springs, and Challenger III rolled out of his shop on a third. Challenger III was missing its oversized fuel tanks when he acquired it from Bragg; so the tanks used in the restoration were taken from Challenger I.

The interior is unusually complete for a race car. All surfaces are upholstered, trimmed and color-coordinated to production-car standards. The floor is fully carpeted. The stock Futura inner door panels, inconspicuously shortened three inches at the bottom, retain their deluxe armrests. The custom instrument cluster is set into a stock dashboard with a fully functional glove box. Vinyl-covered panels conceal the enormous twin fuel tanks. Were it not for the stark, four-spoke race-car steering wheel – and the full roll cage – this could easily be the interior of a lusso GT import.

The restoration also revealed that Challenger III “had always been cared for,” said Ida. “We didn't have to deal with rust. It was clean, solid, and very complete. Beyond fabricating and replacing a few brackets, no new welding was required. And Ted had done a lot of work already, and that made it easy for us.” Thomas had even commissioned a custom-built 289 with a Holman-Moody-spec camshaft and valve train, which arrived at Ida's shop in its original crate.

Kroplick asked Ida to “bring the car back to what it looked like when it raced in the Bahamas.” As it turns out, one of the few surviving color photos of Challenger III shows three Holman-Moody technicians inspecting it in the Nassau paddock. Years earlier, Thomas had painted the body shell Ford Viking Blue, to match the Nassau photo, but rather than touch up some “bumps and bruises” Ida stripped and resprayed the body the same color. Jennifer “Hot Rod Jen” Thomas was hired to recreate the Nassau graphics, and Holman-Moody provided replacements for the original “license plates.”

The restoration was completed in November of 2021. In May of 2022 Kroplick displayed Challenger III, reunited with Mustang III, at the Gold Coast Cruisers Waterfront Car Show in Glen Cove, New York. That September, Kroplick and Challenger III were invited to The Bridge, a curated concours on the site of the long-gone Bridgehampton road course.

Thomas, meanwhile, has nearly completed a re-recreation of Challenger I, using the original parts he obtained from the Clawsons. And he believes he knows the whereabouts of the Challenger II body.

Could we someday see all the Challengers reunited and once again confronting the Ferraris -- on the show field, at least, if not the race track? Never say never.

________________________________________________________

(With thanks to Howard Kroplick, Ted Thomas, Tom Cotter, Lee Holman, Rod Ida of Ida Automotive, and Jen Wolfe of the AACA Library & Research Center.)

*Holman & Moody, Inc. frequently shortened its name to “Holman Moody” or Holman-Moody on its products and in its literature. Another variation, “Holman and Moody, Inc.,” appears on Challenger III's manufacturer's plate, just a few lines below “Holman Moody.” Contemporary journalists used all variants

Comments

Fascinating history. And a reminder that so much of what ends up in production cars was first worked out in race cars, something the big 3 forgot, at least for a few years.