1906 American Elimination Trial

Favorite Locomobile Wins the Second American Elimination Trial

Location: Nassau County, Long Island, New York

Date: Saturday, September 22, 1906

As in 1905, an American Elimination Trial determined the five racers to represent the United States in the Vanderbilt Cup Race. Of 16 entries, 12 cars survived the practice runs to race on Saturday, September 22, 1906.

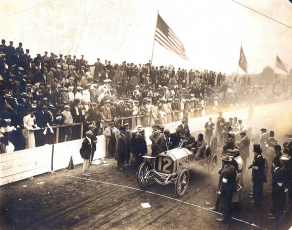

The race was scheduled for ten laps, up from just four in 1905, for a total of 297 miles. With everyone in place a crowd larger (by some accounts estimated at 100,000 ) than the one for the 1904 Vanderbilt Cup Race eagerly awaited the start.

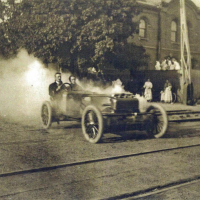

The American Elimination Trial Start

With Ernest Keeler in an Oldsmobile first in line at the tape as the 6 a.m. start drew near, the grandstand crowd craned their necks to get a better look as a hush of expectancy fell over the setting. Keeler’s mechanic Harry Miller cranked their Oldsmobile engine. Miller would go on to become one of the most successful auto racing designers of all time, with his cars dominating the Indianapolis 500 and other races in the 1920s and 1930s.

Wagner counted off the minutes until precisely at 6 a.m. he gave the word to go. Keeler’s start was slow, apparently faltering with the gearshift. A minute elapsed before the next starter, Herb Lytle with Bert Dingley, this year serving as riding mechanic in the Pope-Toledo, was given the starter’s command. Like Keeler, Lytle also got away slowly, gradually picking up speed.

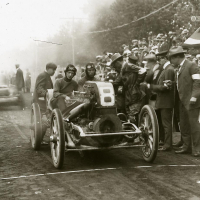

Officials, photographers and other hangers-on surrounded each team in the nervous seconds leading up to their send-off. Driver Ralph Mongini, a former opera singer, arrived at the line and was described by Motor Age as “too handsome for a brown knickerbockers suit.” Mongini sported a tapped wrist due to an injury from a twist of the wheel in practice, but got away in what most judged the best start of the day in the red Matheson.

The starting order next called for Gustave Caillois, the first of two French drivers hired to steer Thomas entries. Wagner counted off the seconds leading to his start time, but Caillois was parked 100 feet from the starting line as his driving teammate Hubert Le Blon and a mechanic lay under the car adjusting the drive chain. Caillois lost 25 seconds before he started.

The Maxwell entry, which was to be driven by Wallace Owen, never appeared at the tape due to a crankcase failure the day before in practice. Still, Wagner maintained the starting spot, counting down the reserved time for Owen’s start as if the Maxwell might appear at any second.

A second Maxwell originally planned for driver J. Fred Betz, also failed to show. That car was never assigned a number as it never appeared on course for practice due to insufficient testing.

This created an additional minute interval before the next starter, Le Blon, in the second Thomas, was to be sent away. The third Thomas, for Montague Roberts, followed Le Blon, starting sixth. Much was expected of the three Thomas cars as they borrowed heavily from French design, assisted by the two Frenchmen hired to drive.

Le Blon suffered a setback, losing 26 seconds when the Thomas engine did not immediately respond to cranking. Completing the string of Thomas bad luck, American driver Montague Roberts was 9 seconds late getting away in the company’s third entry, his head under the hood of his racer when Starter Wagner began counting.

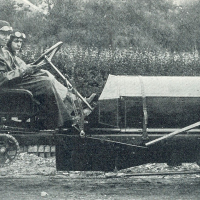

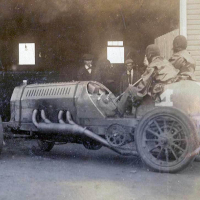

The seventh starter was the first of three Frayer-Millers with Lee Frayer at the wheel. Unlike any other make of car, the Frayer-Millers placed the driver on the left side. The constructors theorized that this would better balance the cars on the predominately left turn course.

Beside driver Lee Frayer in the Frayer-Miller was arguably the most significant historical figure present that day, 16 year old Eddie Rickenbacker, who later drove in the Indianapolis 500, became America’s most famous fighter pilot of World War I, purchased the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and eventually became chairman of Eastern Airlines. Rickenbacker would return to the Vanderbilt Cup Race nine years later in 1915 as a driver and captain of the Maxwll team. Frayer made a smooth start.

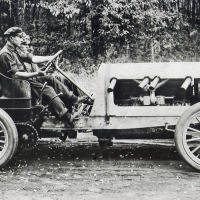

Walter Christie and his blue front wheel drive Christie touring car entry got away well as the eighth starter, a far different story than the year prior when he started the Vanderbilt Cup Race 30 minutes late. Christie originally intended to run a purpose-built Christie racer but those plans were scuttled the day before the Elimination Trial when he clobbered a telegraph pole during practice. He and riding mechanic Louis Strang – who went on to drive in the inaugural Indianapolis 500 – were uninjured. The cause of the collision with the pole was traced to a steering gear that had been damaged the previous day – Thursday, September - in a relatively minor accident. Christie and Strang decided to start the car on the last day of practice (Friday, September 21) because they were having trouble with a sticky clutch and believed moving the machine would release it. Too late they discovered the steering was useless and they hit the pole.

The second Frayer-Miller, driven by Frank Lawwell, was released next after an additional minute was added to the standard 1 minute interval to recognize the absence of George Robertson’s Apperson entry. Robertson had survived a horrendous accident while practicing the previous Wednesday , literally wrapping his car around a tree.

Driver Lawwell and his mechanic Charles Eckhardt had signal whistles tied to one end of handkerchiefs that were sewn to the peak of the hoods they wore on their heads. The exact purpose of the whistles was unclear, but almost certainly involved communication between each other or their team.

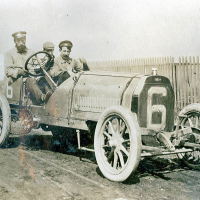

Christie had received an especially encouraging round of applause, but it proved to be nothing to match that given crowd favorite and ninth starter Joe Tracy in the Locomobile. If by no other measure, the sound of the applause was an indication that he was the crowd favorite.

The absence of another entry, called the BLM, was recognized with the additional minute interval after Tracy’s departure before releasing the next car into competition. The BLM car was owned by three wealthy young men of socially prominent families: Breese, Moulton and Lawrence. The car was reported to have cracked a cylinder when en route to the course days earlier.

The final two starters were the Haynes and the last of the three Frayer-Millers. Englishman E.N. Harding, an eleventh hour replacement for John Haynes in the Haynes entry, was next. Established as a Daimler driver in various racing and hill-climbing events, Haynes believed Harding’s experience gave the team an extra edge.

The twelfth and final starter, Richard Belden, in the last of the Frayer-Millers, startled the crowd when his car stumbled at the start. He had forgotten to release his hand brake and the car faltered. After releasing it, he sped away, fully 14 minutes after Keeler in the Oldsmobile.

Lap 1

The first lap took a steep toll as four of the 12 starters suffered severe setbacks. The first casualty was Roberts in the Thomas who snapped a rocker arm on one valve after traveling barely 200 yards. He crawled around the course to the Thomas garage at Krug’s Hotel in Mineola. By that time he damaged the transmission, requiring a replacement. The entire misadventure cost him 3 hours.

Lytle in the Pope-Toledo quickly overhauled first starter Keeler in the Oldsmobile. The Oldsmobile had developed a blowhole in its carburetor, destroying the gas-air mixture fed into the engine cylinders. Keeler stopped between Jericho and East Norwich to try to patch it with gum, but it was useless. It would be 1 hour and 40 minutes before he would complete a lap.

Lee Frayer, driving with Eddie Rickenbacker, broke a radius rod in their Frayer-Miller near Roslyn and was done for the day, ending up last among those that started. Mongini in the Matheson proved a flash in the pan. He had taken the lead early on, and shaved off all but 10 seconds of Lytle’s 1 minute head start by the time they reached the hairpin turn in Old Westbury. Steadily gaining ground as they approached Manhasset Hill, Mongini in the 60 horsepower Matheson touring car was hot on the heels of Lytle’s racing Pope-Toledo.

But that was as far as Mongini would go as he got the Matheson out of shape on a corner leading up to the hill, nearly driving the car off the road. The skidding blew a tire and he slammed into a telegraph pole.

Mongini and mechanic John Green were thrown 15 feet from the car and one report indicated the driver hit his head on the telegraph pole, briefly rendering him unconscious. When he awakened, he was dazed and repeatedly asked the growing crowd around him what happened.

The Matheson ended up in a ditch with one of the rear wheels hooked around the pole. Mongini wanted to forge ahead but when Matheson team manager Tom Cooper and owner C.A. Singer arrived they decided too much time had been lost to try to continue.

Crowd favorite Joe Tracy encountered a setback when his Locomobile suffered a flat tire and had to stop at the Diamond tire depot near the hairpin turn in Old Westbury. The replacement required only 4 minutes. Beldon in the third Frayer-Miller had tire trouble as well. Caillois’ Thomas suffered magneto failure and reported to the team’s Mineola garage.

All of this action was happening well out of the sight of those at the Westbury grandstand. While track announcer Peter Prunty bellowed through his megaphone reports fed to him from 25 telephone stations around the course, people were eager to see who would come back around first.

Tension built as a half hour elapsed since Keeler’s Oldsmobile departed, and everyone knew the leader would appear soon. Within minutes the bugler atop the officials stand blasted his warning and the crowd leaned forward to see Pope-Toledo driver Lytle appear, recording his lap at an average of 55.0 miles per hour.

Not only was Lytle first to come into view, but also he was clearly well in the lead as it was 5 minutes before the next driver to arrive, Le Blon, in the Thomas, roared onto the scene. In a surprise, Walter Christie and his blue Christie touring car completed the lap in second place averaging 53.9 miles per hour.

Laps 2 and 3

Lytle in his Pope-Toledo expanded his advantage on the field by recording his fastest lap of the race at 55.2 miles per hour during lap 2. Le Blon moved his Thomas into second as he, Tracy (Locomobile) and Harding (Haynes) all took advantage of a delay for Walter Christie to adjust his clutch.

Beldon had another disappointing lap with his Frayer-Miller, this time enduring a long stop to sort out a wiring problem. Keeler pulled his white Oldsmobile off the course on the stretch leading to Manhasset, his faulty carburetor finally ending his day.

Again on lap 3 Lytle’s white Pope-Toledo appeared first at the start-finish line, but this time he was in second place. Le Blon in the Thomas had closed well within Lytle’s 4 minute head start on him and now led by 21 seconds. Seven minutes later came the Joe Tracy’s Locomobile, placing him firmly in third place, well ahead of Harding, who held fourth despite a tire change stop for the bright green Haynes. Christie remained in fifth. Caillois, in the other Thomas, still recovering from his disastrous first lap, pulled together his second consecutive strong lap, overhauling Lawwell in the Frayer-Miller for sixth.

Lap 4

Weather threatened the event as ominous clouds pelted rain on the grandstand elite as many scurried for cover. Fortunately, the rain quickly ended.

Boredom, too, settled in as just nine cars remained circulating the 29.7-mile course. A band, present for such lulls, struck up the tune, “Waiting at the Church.” Earlier, Willie K and friend Harry Payne Whitney sang the song, triggering impromptu quartettes throughout the stands belting out popular tunes of the day, such as “Give Us A Drink, Bartender.”

On the track the field dwindled but the battle among the leaders got more interesting. Tracy, Le Blon and Lytle raced in earnest, with the Locomobile turning in what would prove to be the second fastest lap of the race averaging at 59.8 miles per hour. Now Tracy’s Locomobile led Le Blon in the Thomas by nearly 18 seconds, despite the latter turning his fastest lap of the race. Lytle was the only other serious threat, about 2 minutes back.

When Lytle’s Pope-Toledo came across the line there was a distinct scent of burning rubber as he had one flat tire. His tire was described as “in rags,” slapping against his change gear, which damaged the mechanism enough to make gear selection difficult. He drove on the rim for some 7 miles, eventually stopping at a Diamond tire station near Jericho, where he lost time as mechanics straightened kinks in his damaged rim.

Walter Christie soldiered on in fifth, fighting tire trouble. He held an important advantage in this regard, though, due to his work in developing removable rims similar to the Europeans, which allowed him to change a tire in under a minute and a half, lightning fast in the day. That advantage was quickly lost as Christie also endured nagging clutch and carburetor problems.

Lap 5

Joe Tracy kept a scheduled stop at his Locomobile service station near Bull’s Head Hotel in Greenvale on his fifth lap to take on fuel and water. The stop cost him the lead and he dropped to third behind Le Blon and Lytle.

While Le Blon recorded a trouble-free lap with his Thomas, Lytle began showing telltale signs of a malady that would prove his undoing. His radiator sprung a leak, which would necessitate subsequent stops.

Some speculated that the pounding Lytle’s Pope-Toledo took driving for several miles on a flat tire over the crushed stone surface the lap before had caused the damage. One colorful story had a farmer’s wife rushing to Lytle’s aid with a package of rolled oats to pour into his radiator. As the oats mixed with the hot water they swelled and helped slow the leak.

Frank Lawwell’s struggling Frayer-Miller broke a fuel pipe and mechanic Charles Eckhardt leaned out over the front of the car to pour gasoline directly into the carburetor using the cover to the car’s coil box. This he did at regular intervals to keep the engine from stalling.

Belden’s Frayer-Miller was finally done when a wheel collapsed near Roslyn. The car had been so slow Tracy almost collided with it near the hairpin turn.

“We were following closely after Belden in the Frayer-Miller, when he stopped short with his engine dead and his brakes on. There was just room for the Locomobile to squeeze through between the other car and a telegraph pole.”

Roberts, too, was finished in the third Thomas entry. A faulty gasoline tank and more transmission trouble were the crushing blows.

Lap 6 and 7

Tracy reeled off the fastest lap of the race with the Locomobile on his sixth tour of the course, the only time anyone topped 60 miles per hour. With a lap time of about 29.5 minutes, he overhauled the Thomas of Le Blon who suffered a setback when the float of his carburetor caught fire at Lakeville and he pulled to the side of the road and smothered the flames with dirt.

Lytle had a disastrous lap, his race unraveling fast. His Pope-Toledo’s radiator continued to hemorrhage water and his engine began to show signs of slowing due to overheating. He also had to change two tires, which cost him additional time as he lost nearly an hour to Tracy and Le Blon. The delays robbed him of third place, as Harding pushed past him. This was true despite Harding’s stop to replenish gasoline and water in the Haynes.

Lap 6 proved to be Caillois’ final tour, his problematic Thomas breaking the pin of his magneto on the North Hempstead Turnpike. Only a lap earlier he had finally clawed his way into the top five positions that would qualify for the big race.

The wear of the race showed on the surviving machines during lap 7. Thomas driver Le Blon regained the lead when Tracy’s Locomobile experienced a mechanical problem. Pieces of solder inside the gas tank broke loose and clogged the line to the engine. Riding mechanician Al Poole required 3 minutes to extract them. The Locomobile team lost additional time refilling the radiator. Poole was seen screwing down the radiator cap while hanging onto the hood with the car at speed just beyond the hairpin turn.

Lytle’s Pope-Toledo continued to struggle with a slowing engine as he recorded his second consecutive lap at over an hour. His radiator leaked like a sieve, spilling the precious water his melting engine desperately needed into the oily dirt.

Harding’s Haynes touring car proved a steady performer, still pulling away from the struggling Lytle and Christie. Christie’s touring car required repairs to a faulty steering gear slowing his seventh lap time to nearly an hour and a half.

An almost comical scenario developed in the saga of Lawwell and the Frayer-Miller. His faulty carburetor finally stalled his engine at Lakeville. He then took a bicycle to get to Mineola, where he acquired a can of gasoline and a bottle. Riding mechanician Eckhardt then straddled the engine pouring gas into the carburetor with the bottle, which he filled repeatedly from the can. This sight got a rise from the grandstand as the Frayer-Miller stormed by. –

Laps 8 and 9

The race evolved into a seesaw battle between Le Blon in the Thomas and Tracy in the Locomobile. Tracy was clearly gaining, but it was a game of inches. With Le Blon up barely 33 seconds and unexpected stops consuming minutes, there was no margin for error.

Third place Harding’s Haynes developed problems when the car’s hood came loose and sheared the water pipe. His mechanic tried a makeshift repair job with a handkerchief.

The Pope-Toledo crew made a fateful decision during lap 8 that would eventually deliver a fatal blow to their aspirations of representing America in the upcoming international race. On one of Lytle’s numerous stops to replenish water at the Pope-Toledo headquarters at Bull’s Head Hotel they towed the car for about a quarter of a mile to get it started. This was a clear violation of rule 42, which forbade such assistance. The decision was made because an attempt to hand crank the motor had failed.

The Frayer-Miller team finally replaced Lawwell’s damaged carburetor. The car picked up significant speed, recording the lap at just over 33 minutes, which was less than 2 minutes off leader Le Blon’s pace in the Thomas.

Lap 9 proved to be the pivotal point of the race as Tracy surged his Locomobile to the front after mechanical problems delivered devastating blows to Le Blon’s chances of victory. First, the Frenchman punctured a tire and stopped for help at a Diamond tire service station near Old Westbury. His Thomas used the new detachable rims and the crew there struggled to figure out how to work with them.

Le Blon was very frustrated with the men and even claimed they stopped their work to watch Tracy pass by. One report estimated that he lost 7 minutes in the incident.

Le Blon’s woes continued when his gasoline feed stopped at Krug’s Corner in Mineola. Le Blon and his mechanician determined that solder resin had clogged the pipe and they extracted it by removing the tube and blowing through it. The problem returned in just a few miles and they went through the same process once more.

While Le Blon suffered frustration with his Thomas, Tracy carried on full tilt. Motor Age said of his drive that, “Speed, courage and luck were to decide the fate of the day.” It was a fair summation, too, because in the end it was Tracy’s willingness to push his Locomobile over the rough course at full speed in the face of Le Blon’s struggles that spelled the difference. Tracy was the first car to complete the lap, with Le Blon appearing 15 minutes later.

Harding, running a distant third, struggled with the Haynes. The handkerchief patch to his severed water pipe proved inadequate, forcing the team to splice it with a hose. He also incurred a punctured rear tire and the two repairs caused a 7 minute delay.

With his Pope-Toledo still bleeding water, Lytle managed his fastest tour of the course since lap 5. His time was just under 40 minutes. The ailing cars of Christie and Lawwell’s Frayer-Miller failed to complete lap 9 before the race was called.

Lap 10

An eruption of applause from the grandstand greeted Joe Tracy when his Locomobile crossed the finish line. Men screamed and waved hats and women stood on their seats and, in the custom of the day, waved handkerchiefs. Tracy’s reputation grew larger with this victory following his third-place finish in the Vanderbilt Cup the year prior.

Known as a reserved man, Tracy offered a characteristically understated assessment of his accomplishment. He said, “There isn’t much more to say except that the car ran well and didn’t have to be nursed. I knew I could speed the engine up without danger. Poole was of great assistance in winning the trial. Of course, we are glad we won; it was our turn.”

Le Blon’s Thomas did not appear at the finish for another 30 minutes, 23 minutes and 42 seconds behind in cumulative running time. The nagging gas feed problem stopped him again, this time at the hairpin turn. The repair required another 10 minutes.

Harding followed in the Haynes, and while Christie (Christie), Lawwell (Frayer-Miller) and Lytle (Pope-Toledo) were still running, referee Vanderbilt called the race as rain appeared again and observers telephoned reports of people crowding the course. Lytle barely completed his ninth lap and was on Jericho Turnpike when his Pope-Toledo’s radiator forced another stop. Shortly afterward he got the word the race was stopped and that he would be one of the five entries of the American team for the Vanderbilt Cup Race.

Disqualification of the Pope-Toledo

On the Tuesday night after the race, when the race commission met to hold the drawing for starting positions in for the Vanderbilt Cup Race, a protest was filed against the Pope-Toledo team. Immediately after the 9 p.m. meeting was called to order, the Frayer-Miller team submitted the protest based on eyewitness accounts of the Pope-Toledo receiving a tow to get started after a service stop on lap 8.

Colonel Albert Pope was praised for his forthrightness, freely admitting that the tow did take place. Pope even apologized and said if the tow was in violation of the rules, then he had nothing to say in his defense.

The regulation in question was rule 42, which forbade the starting of cars at any point in the race by any method other than the car’s own power. With Pope’s confession, the Vanderbilt Cup race commission found that his car was disqualified and the Frayer-Miller would be one of the five American entries.

Rollin’s granddaughter Betty King had this medal. She said she gave it to the National Inventors Hall of Fame Museum…