The Mulford Special: “A Roadster That Saved a City”

Five years ago Wendell McCrady Jr. purchased a unique roadster that most believed no longer existed. The Mulford Special car was one of seven prototypes built by Ralph Mulford, veteran of the 1910 Vanderbilt Cup Race and ten Indy 500 Races (1911-1922). The roadster was highlighted in the May 27, 2011 issue of the New York Times:

From Racer in First Indy 500, a Roadster That Saved a City

By STUART WARNER

New York Times

Published: May 27, 2011

COPLEY, Ohio

MAYBE it is Wendell McCrady Jr. who best understands the value of the rust-speckled roadster tucked away in a storage shed in this Akron suburb.

Not the monetary value of the car, built by a Brooklyn-born racing driver who some still argue was the actual winner of the first Indianapolis 500-mile competition a century ago this weekend. But what the car meant to people like Mr. McCrady who grew up in Akron, the town that became known as Rubber City.

“I guess,” said Mr. McCrady, a concrete finisher who now lives in Copley, “I might not exist if it hadn’t been for that car.”

The explanation, a tale rich with history, takes nearly as many turns as some races.

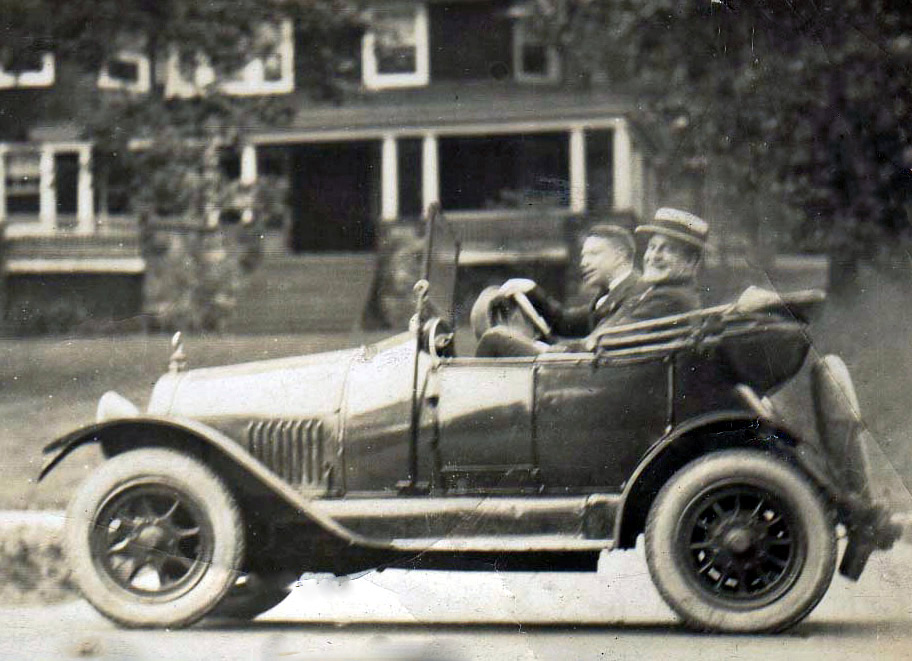

The car is a 1917 Mulford Special Roadster. The 10-foot-long, two-seat runabout was built by Ralph K. Mulford, the driver credited with finishing second to Ray Harroun in the 1911 Indy 500.

The car is a 1917 Mulford Special Roadster. The 10-foot-long, two-seat runabout was built by Ralph K. Mulford, the driver credited with finishing second to Ray Harroun in the 1911 Indy 500.

Mr. McCrady, 56, found the Mulford Special in a barn five years ago and became consumed with lifting the car, its builder and its story out of obscurity.

Mulford was an early racing hero, according to the historian Joseph Freeman. Mulford will be included in Mr. Freeman’s yet-to-be published book, “Second to One” (Racemaker Press, Boston), about the drivers who missed out on Indy immortality in finishing no better than second place.

Mulford was a fierce competitor on the track, twice winning national driving championships. But he was also “a sportsman, a real gentleman away from it, a religious man and a Sunday school teacher,” Mr. Freeman said in a telephone interview.

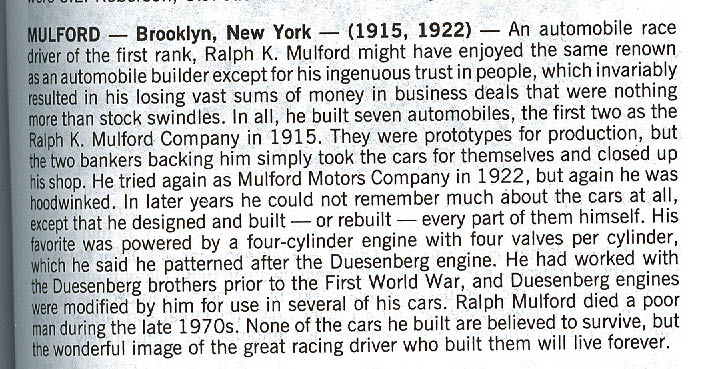

As an automaker, Smiling Ralph, as Mulford was called, was less successful. Reports show that he twice tried to start his own company, building two cars in 1915 and five more in 1922, but both times the businesses failed.

In between, in 1916 and 1917, he built two cars for personal use, a four-seat sedan for his wife and a two-seater with an Opel body for himself, according to a letter he wrote years later. He traveled to Akron and elsewhere looking for proper tires for those cars, he later testified.

Fast-forward to 1925. On May 12, a Michigan inventor, Alden L. Putnam, received a patent for low-pressure balloon tires — larger than earlier tire designs and containing a greater volume of air — similar to those being made in Akron, according to Detroit newspapers. By then, the B. F. Goodrich Rubber Company of Akron was promoting its Silvertown Balloons to “cushion yourself against rough travel.” And after Peter DePaolo won the 1925 Indy 500 on Firestone balloon tires, they became the talk of the industry, Mr. Freeman said.

Three years later, the Steel Wheel Corporation of Detroit, which had acquired Putnam’s patent, filed suit against Goodrich. Steel Wheel demanded that Goodrich stop producing the balloon tires and asked for reparations on the tires already sold.

“Should the court ruling favor the Steel Wheel firm, millions of dollars in damages will be involved,” The Detroit Free Press reported. Moreover, a victory against Goodrich would have brought similar suits against other Akron tiremakers, including Goodyear and Firestone.

That dire situation never came to pass. Testifying that he had bought the balloon tires fitted to his roadster in 1919, years before the patent was approved, Mulford became the savior of Akron’s rubber industry.

Moreover, he testified, he had found similar tires when he visited Goodyear's plant in Akron. “Since there’s no name of a tire like these, I’m going to suggest we call them balloon tires,” he told Goodyear officials, he said.

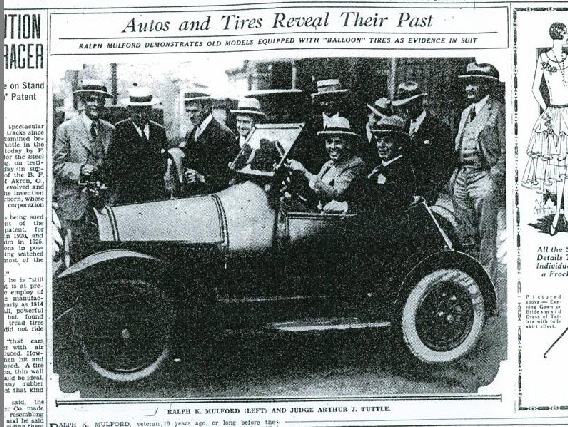

In June 1928, United States Judge Arthur Tuttle ruled in favor of Goodrich. After the verdict was read, the judge went for a spin in the roadster with Mulford. Then the little car and its story all but disappeared.

In June 1928, United States Judge Arthur Tuttle ruled in favor of Goodrich. After the verdict was read, the judge went for a spin in the roadster with Mulford. Then the little car and its story all but disappeared.

Almost two decades later, Goodrich workers found the Mulford Special in a plant building in downtown Akron. They were preparing to throw it out when a former Goodrich employee, Rex T. Brown, recognized the car from the trial, The Akron Beacon Journal reported, and bought it. Mulford confirmed in a letter to Mr. Brown in 1953 that the roadster was indeed the car from the 1928 Detroit trial.

Mr. McCrady bought it in 2006. He had never been a collector of antique cars, he said, preferring Chevrolet Corvettes, but he became fascinated by the histories of the car and the man.

Mulford was inducted into the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame with the class of 1953-54. He died in 1973 at age 88. According to Mr. Freeman, the historian, Mulford continued to make a steady living with a repair garage in his later years. Neither of Mulford’s grandsons, Ralph Mulford III or Jeffrey Mulford, returned repeated calls for comment.

Mr. McCrady keeps the car out of sight. Its 1914 Chevrolet engine has not been started in about a decade, and the tires from the trial were replaced long ago. The original blue paint is worn, and it wears a substantial coat of rust. The roadster’s most distinguishable feature may be its double-pointed fenders.

In its February 2009 edition, Hemmings Classic Car confirmed that Mr. McCrady had found the last known Mulford car in existence. Mr. Freeman reviewed photos of the car for The New York Times and said he, too, is convinced it is the real thing.

“I even remember seeing a handwritten note from Ralph Mulford mentioning that was the car that he took to Akron,” Mr. Freeman said.

Once the identity of the car was verified, Mr. McCrady began a mission to let the world know about the Mulford’s historical significance.

“If Goodrich had lost that case, the tire industry in Akron might have collapsed,” Mr. McCrady said.

But very few people, even in Akron, seem to know much about the case.

John D. Ong, a chief executive of Goodrich in the 1980s and ’90s, said in a telephone interview that he had not heard the story. He consulted the company’s official history book and found nothing. “Wheels of Fortune” (University of Akron Press, 1999), a history of Akron’s rubber industry, made no mention of Mulford or his roadster.

Finally, in 2008, The Akron Beacon Journal told Mr. McCrady’s tale, calling the Mulford Special “the car that saved Akron.”

And that begins to explain why Mr. McCrady says he believes he owes his life to the car in his storage shed.

His father, Wendell McCrady Sr., was one of the thousands of West Virginians who had moved to Akron to work at the tire companies. He got a job at Goodyear after World War II and met his wife, Mary Jane, at Summit Beach Park in Akron.

So if Goodrich had lost the 1928 case, and the city’s tens of thousands of rubber jobs had been wiped out, “I probably never would have been born,” Mr. McCrady Jr. said.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: May 29, 2011

An earlier version of a summary of this article misstated the history of the roadster built by Ralph K. Mulford, who finished second in the first 500-mile Indianapolis race. The roadster, built in 1917, is not a racecar and was not the car that was driven by Mulford in the 1911 Indy 500.

A version of this article appeared in print on May 29, 2011, on page

From the standard catalog of American Cars 1805-1942 @1996 Krause publications

If you have any information about the Mulford Specials, Wendell McGrady Jr. would like to hear about it. Any comments would be much appreciated.

Links to related posts on VanderbiltCupRaces.com

Archives: 1910 Vanderbilt Cup Race

Comments

I appreciate this great story, especially since I had never heard of this before.