The D.W. Griffith Vanderbilt Cup Race Film That Almost Was

In 1910, D.W. Griffith, the pioneering American director, proposed to create an innovative racing film for American Biograph & Mutoscope . Using the Vanderbilt Cup Race as the backdrop, Griifth wanted the film narrative to highlight "triumph over adversity and competitve rivalry". Andrew Gray has documented Griffith's proposal in this Screened.com post (supplemented by my films and images):

The D.W. Griffith Auto Racing Film That Almost Was

By Andrew Gray

When the Vanderbilt Cup automobile races started in 1904, the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company (later known as Biograph Films) received a contract to film newsreel footage. Biograph cameramen G.W. Bitzer (later D.W. Griffith's cinematographer) and A.E. Weed set their motion picture cameras alongside the still photographers in designated press boxes.

They captured the Long Island race's start, finish, and important turn. Biograph continued to film Vanderbilt Cup races between 1905 and 1909, doubling the number of cameras. However, there was one problem with the racing films produced by Biograph. They were horribly boring.

They were two and a half minute reels of similar-looking cars trundling from one side of the screen to the other. Slowly. The average speed of a race car in the early 1900s was between 50 and 60 miles per hour. Adding to the problem, camera placement did not depict the racers anywhere near top speed. Most eyewitness accounts stated that the races were thrilling in person. Race cars bounced on unpaved dirt roads with the constant threat of mechanical failure or plowing into the unguarded crowds. However, audiences yawned at the films. Some audiences even reported that they thought that the films repeated the same race car over and over. Biograph's films were clinical reports of a race -- akin to security camera footage.

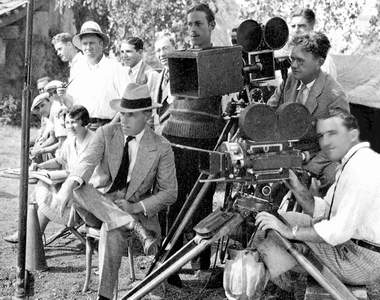

To rectify this problem, Biograph approached their staff director D.W. Griffith to film the 1910 Vanderbilt Cup. Griffith was famed for his pioneering narrative techniques in cinema: close-ups, moving cameras, and cross-cutting edits. He would go on to direct such early cinematic epics as The Birth of a Nation and its apology Intolerance. Biograph felt Griffith was the man to turn footage of cars going fast into something interesting. Griffith, a very proud man, agreed.

As with almost everything he did, Griffith wanted to go grandiose with the project. He had experience with cars on film. A year prior, in 1909, he made The Drive for Life. This film included scenes of a man driving quickly to warn his fiancée about a poisoned candy revenge plot, overturning carriages and crushing cameras along the way. Griffith believed that the urgency of the scene precipitated the sense of speed. He felt motion pictures communicated emotion. The emotion in a racing film was excitement derived from speed. Griffith had many, radical ideas on how to communicate this excitement, ranging from narrative to technology.

Griffith held that racing films needed to tell a story. He wanted to make protagonists by differentiating the cars with their individual drivers. To accomplish this, Griffith wanted to cut between film of a car mid-race and close-ups of its drivers. He also wanted to establish the geography of the race to create an antagonist by demonstrating the perils of the course and the temperamental automobiles. The narrative was to emphasize triumph over adversity and competitive rivalry.

In addition, camera technology had to be improved to convey velocity. New film stock needed different speeds to create the correct type of motion blur. Zoom lenses with variable focal lengths needed to be developed to emphasize points of interest. Griffith also imagined methods of placing the audience in the action. He proposed plans for attaching cameras to the race cars, both behind the drivers and on the grill. There were thoughts of chase cars following the racers as well. This technology was within reach but expensive.

Biograph turned down Griffith's proposal in its inception. Aside from Griffith's ideas requiring a large sum of money, editing the race footage with a specific narrative intent was considered an invalidation of the film as a news piece and historical artifact. Griffith departed the Vanderbilt Cup project and began work on another, non-documentary Biograph feature. Griffith's concepts about speed on film remained theoretical for years, until other directors and producers started to dream big. In essence, D.W. Griffith was saying, "You mustn't be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling." Did I just type that?

Four years after Griffith's proposal, Mack Sennett used a similar racing narrative in his slapstick commedy film Mabel at the Wheel starring Mabel Normand, Ben Turpin and Charlie Chapin. I consider it the best known documentation of the 1914 Vanderbilt Cup Race held in Santa Monica, California:

Links to related posts on VanderbiltCupRaces.com and the Internet:

Archives: Vanderbilt Cup Races- Films, Videos and Slideshows

Comments